Capitol Beach: Rich in History

by Julie Nichols

A mile or so west of the Haymarket on the west edge of downtown Lincoln, Capitol Beach is a quiet neighborhood bordered by restored saline wetlands—its colorful history invisible. No evidence remains of the stream of entrepreneurs and big dreams. No sign remains of the lost joys of roller coaster rides, dances, swimming holes and a beautiful steamboat called the Belle of the Blue. A tangle of land disputes, shady real estate deals, a governor’s impeachment, the rise and demise of a popular resort all began with the oddity of a crystalline landscape draped with the illusion of water—and the promise of the riches of salt.

“Approaching Lincoln from the east, the first remarkable object that meets the eye of the stranger is a succession of what appear to be several beautiful lakes…,” an account from 1861 states. “As their crystal surfaces glisten like molten silver in the sunlight the illusion is complete, and the most critical landscape painter would be deceived as to their character…there is no water enclosed in their grassy banks.”

The vast area was a salt basin: “hard clay, smooth and level as a brick-yard and polished as that of a Hollander’s kitchen.”

For centuries, indigenous people and animals visited the salt basin to provide for their needs. As European settlers traveled westward, the promise of salt to preserve food detoured them for as far as 100 miles to obtain it from the well-known basins. In those days, salt was legal tender, as was flour. Some “salt pilgrims” stayed to ply trade in salt, scraping and refining it through primitive evaporation techniques. An informal industry sprang up, and with it a village called Lancaster, population 30. Based on the promise of limitless salt, the new territorial capital was sited near the banks of Salt Creek and renamed Lincoln.

Land patents, warrants and a flurry of questionable leases made rights of use a legal brawl, and Nebraska’s first territorial governor, David Butler, was drawn into the fray, leasing the basins to one Anson C. Tichenor. Without sufficient timber to heat and evaporate brine, and with productive salt mines in nearby Hutchinson, Kansas, Tichenor realized salt was not a winning proposition and unloaded the property on Horace Smith (of Smith and Wesson). Tichenor then built a large hotel, with Gov. Butler as enthusiastic cosigner, to house visitors and new legislators flocking to the capital. Tichenor skipped town for California, leaving an outstanding mortgage, partially financed by Gov. Butler—with state school funds. Needless to say, Butler was relieved of his office.

Arbor Day founder J. Sterling Morton, whose son would later found the Morton Salt Co., had conveyed the salt basin lands (through his authority as agent for an eastern owner) to John Prey, the first settler in Lancaster County. Prey, in quid pro quo fashion, issued warranty deeds to Morton and two other partners, one of whom happened to have been the initial surveyor of the property. Morton challenged the authority of Gov. Butler’s salt leases, and although he lost locally, the case was decided in his favor by the U.S. Supreme Court.

By late century, it was abundantly clear that the basins held no “motherlode” of salt, and settlement of Lincoln veered to the east where freshwater sources could support industry and a growing populace. In 1895, new entrepreneurs diverted Oak Creek into the basin’s ephemeral wetlands and created a permanent saltwater lake.

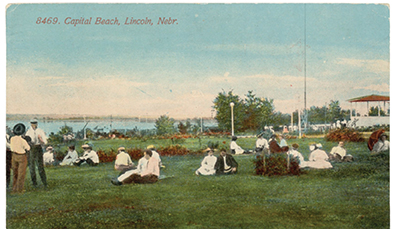

Tons of sand were hauled in to form Burlington Beach, so called because the Burlington Railroad line carried passengers from urban Lincoln to the lake. Restaurants, bathhouses, a penny arcade and fun house drew steady crowds. Among the attractions were steamboat excursions on the 50-passenger Belle of the Blue, a wooden roller coaster and pavilions. “The Coney Island of the West,” as some called it, was said to draw more than 150,000 visitors per year—perhaps based on the crowds in attendance for William McKinley’s campaign speech there in 1896.

W.H. Ferguson, owner of prominent Meadowgold Dairy, purchased the park in 1906 as the lake leaked and drained away. Gradually, Ferguson added more “autorides” and attractions year by year, including a hot air balloon ascension field. Stabilized dikes helped refill the lake. In 1912, the park was renamed Capital Beach. In 1926, a full-sized swimming pool, fed directly from the salt springs beneath the lake, advertised curative powers for ailments including rheumatism, cancer, skin conditions—even fallen arches.

In the 1930s, a movie theater went up, but the second of two wooden roller coasters, the Jack Rabbit, came down, and a giant swing was built. Boats for rent floated on the lake. For a nickel, you could ride a miniature train around the perimeter of the park. The new King’s Dance Hall drew major talents including Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington and the Dorsey Brothers. A lesser-known radio band sponsored by a soft drink company, The Clicquot Club Eskimos, was said to be “something else” and was much beloved by Lincolnites.

Capital Beach—later Capitol Beach— operated uninterrupted from 1912 to 1958. Crowds dwindled, and stock car races became the main attraction. The park officially closed in 1958 and quickly fell to ruin. The rides were removed and the entrance gate came down in 1962. The S.E. Copple family bought the blighted property, expanding the lake into a 350-acre boating lake. Summer homes cropped up on the west side. In 1972, the city approved the building of nearly 1,000 apartments and condominiums with exclusive access to the private lake.

The neon lights and clatter of midway rides may be gone, but people still flock to adjacent Oak Lake Park’s playgrounds for picnics and spectacular fireworks each July 4th. In the heyday of Capitol Beach, celebrations with fireworks were common. One long-time resident reminisced about the lively scene, saying, “We didn’t need a holiday to put on a fireworks show. Just about anything was enough to set us off. And how the people would come!”

While development has obscured the original face of the salt basins, a portion of the original ecosystem was restored in the early 1990s, opening the treasures of a dense and rare saline wetland to the public. Fishers young and old frequent the shores. Walking trails and a viewing blind provide visitors discreet contact with wildlife and the rich variety of waterfowl that frequent the wetland ponds.

From dreams of wealth to broken dreams, from bustling leisure park to bleak decay to a stable residential neighborhood, Capitol Beach’s unusual story remains unique in Lincoln’s history.

Growing up I had friends that had a house on Capitol Beach, I always dreamed of having a house there some day. I drive by there it’s as close as I can get that feels like the Ocean to me. One day!!