The Long Road to a Landmark

by Ed Zimmer

Nebraska’s beautiful State Capitol took a decade to build (1922-1932) and an expenditure of ten million Depression-era tax dollars. More than that, it took three tries to design and construct the landmark building—it’s the third State Capitol to stand on the same grounds between 14th and 16th Streets, H and K Streets. Before paying a verbal visit to the current Capitol, it is worth putting it in the context of its predecessors.

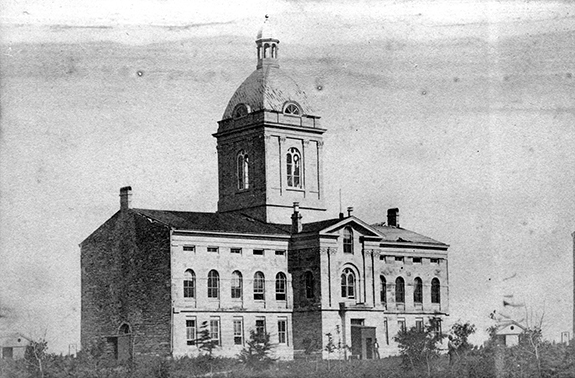

When the tiny town of Lancaster was chosen as the site for the capital city of the new State of Nebraska in 1867, the Capital Commission, which made that choice, also bore the responsibility of providing for a house for the state government. Governor David Butler, State Auditor John Gillespie, and Secretary of State Thomas P. Kennard—that Capital Commission—advertised for designs for a Capitol. They received few responses, which was not surprising as Lincoln—the renamed former Lancaster—had no railroad connection, a handful of residents, dirt roads, and no steamboat access. A design by John Morris of Chicago was chosen over a submission by two Nebraska City men, and Morris was also hired as superintendent of construction. Securing workmen and materials were his major challenges, especially suitable building stone. Construction was accomplished by 1868, using local limestone quarried near Beatrice south of Lincoln, and carted to the site by oxen.

This first capitol faced west, with its longer axis north-south. A 120-foot-high dome rose above the center topped by a cupola, providing a fine vantage point for a photographer to create a panoramic series of images around 1870, showing a scattering of buildings, but mostly prairie, in every direction. It was probably an impressive building in its original setting, and there are indications that the architect envisioned the structure as the centerpiece of a grander building. The north and south walls were left roughly finished of rubble-stone construction, where wings were presumably planned to be attached. A sketch in the corner of an early map of the city probably reflects how the completed building was intended to appear. But the local stone was of such poor quality that it deteriorated rapidly in the weather, and by the time the structure was a decade old, plans were underway to replace it.

Again a Chicago-based architect, William H. Willcox, won the commission for the new structure and its first wing was constructed by 1881, butting up against the original building. The second wing followed, framing the older structure, which was then removed and replaced with the central, domed pavilion of the Second Capitol, completed in 1888. Willcox’s design, like many state capitols, mimicked the U. S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. with its central columns and pediment, crowning dome, and side wings. The lantern atop the dome soared nearly twice the height of the first Capitol.

The Second Capitol served considerably longer than the first, but it too suffered structural problems and was considered small for its purpose by the 1910s. This time, greater attention was paid to creating a durable, monumental structure. Two key steps were appointing a Capitol Commission, and the Commission’s hiring of Omaha architect Thomas R. Kimball as its professional advisor.

Kimball devised an impartial competition with a jury of three leading national architects, a process to select well-qualified architects both from Nebraska and nationwide, and anonymous submissions. Eight of the submissions might be classified as competent variations on the U. S. Capitol model, while two offered towers. One of those was a very bold 400-foot skyscraper, set of a low base nearly 500 feet square. After that design was chosen, its architect was revealed to be Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue of New York City. (The other tower was submitted by one of the three Nebraska architects among the finalists, Ellery L. Davis of Lincoln.)

While Goodhue’s tower perhaps seemed impractical or extravagant at first glance, the proposal allowed for construction of much of the base, providing offices and legislative chambers, surrounding the Second Capitol building. The old Capitol was used until it was supplanted by spaces in the new structure. Then the old building was demolished and the tower and remainder of the base completed. It was a brilliant design, wed to a pragmatic, phased construction plan.

The building of the current Capitol was staged over ten years, beginning in 1922. The long duration was due in part to the sheer scale of the project, but also because of the need to accumulate funds from a special statewide property tax levied specifically to build the Capitol. Sadly, Goodhue died in 1924 at age 55. His associates carried out his vision, seeing the project to completion in 1932.

A central aspect of the Capitol Commission’s charge to Goodhue, which fit closely with his own design perspective, was that the architect collaborate closely with allied designers in creating a unified whole. The carvings of Lee Lawrie and mosaics of Hildreth Meiere are not so much applied to the building as embedded within it. Lincoln landscape architect Ernst Herminghaus designed a subtle planting scheme for the Capitol grounds that creates and enhances views to key aspects of the building. The project even engaged a philosopher, University of Nebraska professor Hartley Burr Alexander, to write inscriptions for the building and to guide the content of the decorative program, emphasizing the historic development of law and civil society. A key aspect of the original design, four fountains as centerpieces of four interior courtyards that bring light and air to inner corridors and offices, were finally installed in 2017.

In a gracious touch, the Goodhue Capitol bears two cornerstones, set into the granite base near the northeast corner. One, crisply inscribed and beautifully designed, is for the third Capitol construction. The other, somewhat battered and worn, was salvaged from the second building and bears the names of the key figures in its construction, including architect Willcox. It took Nebraska three tries, but the final result is a landmark for the ages.

Recent Comments