Lincoln’s Original Plat of 1867

Planting the seed of a well-planned capital city

by Ed Zimmer

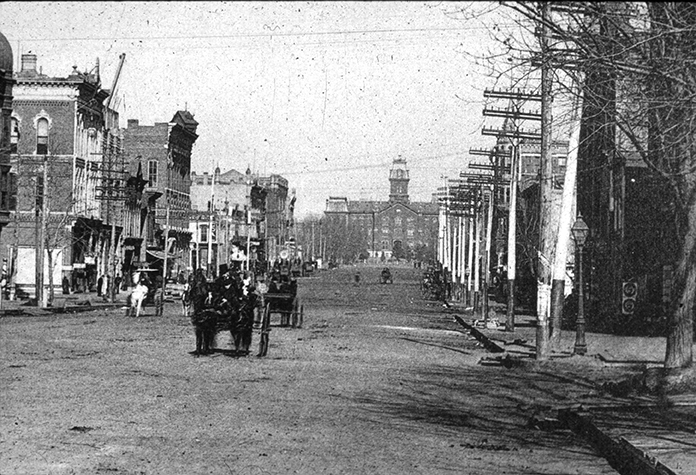

With its grid of east-west streets lettered from A to U and north-south streets numbered from 1st to 17th, Lincoln, Nebraska may not appear to have sprung from a very innovative city plan. But there is abundant good, if slightly subtle, thought woven into the grid of Lincoln’s “Original Plat.”

In 1867 the small settlement of Lancaster in Lancaster County, Nebraska had a population of about thirty, scattered in cabins on a grid of streets in the general vicinity of today’s Downtown Lincoln, Nebraska. Three Nebraska constitutional officers—Governor David Butler, Auditor John Gillespie, and Secretary of State Thomas P. Kennard—had been tapped by the legislature of the new State of Nebraska as the Capital Commission, charged with selecting and launching a state capital city. They chose Lancaster (for reasons that are another whole story), wiped the slate clean, and launched a new settlement, renamed “Lincoln” for the assassinated president.

To give Lincoln a form, they engaged surveyor Augustus Harvey to prepare “A Plat of Lincoln, The Capital of Nebraska.” He laid out a grid of streets from 1st on the west, near winding Salt Creek, to 17th on the east, near the ridge line above the smaller Antelope Creek, meandering approximately a half-mile to the east. The southern boundary was an east-west street labeled “A Street.” Thirteen blocks to the north was “O Street,” assigning that letter to what become Lincoln’s “Main” street and launching a tradition of lame jokes about “Zero” Street. (Harvey skipped “I” in the alphabet, presumably to avoid confusion with 1st Street, instead of using Washington, D.C.’s solution of calling the street between H and J “Eye” Street.) North of O Street, Harvey drew a smaller grid from 7th to 14th and from O Street six and a half blocks to U Street, for purposes that will become apparent.

This simple grid provided 245 blocks measuring 300 feet on each side, most of which were divided into a dozen house-lots, each 50 feet by 142 feet (borrowing 8 feet from the back of each to form a 16-foot alley through the blocks, mostly east-to-west). The plat certainly provided room to grow—nearly 3,000 house-lots for former Lancaster’s 30 residents.

Three “super-blocks” distributed in the southwest, southeast, and north-central areas of the plan begin to reveal the city’s special character. In the southeast, bounded by 14th, 16th, H and K Streets, is Capitol Square—10 acres on which all three of Nebraska’s capitols have stood, in sequence. To the west, bounded by 6th and 8th Streets, D and F Streets, is a 10-acre tract labeled “Lincoln Park.” Now renamed Cooper Park it is the city’s first public park. To the north is University Square, between 10th and 12th Streets, R and T Streets—a campus, ready and waiting two years before University of Nebraska was founded. By assigning to Lincoln not just the Capitol, but also the soon-to-be founded University, the State Prison, and the State Insane Asylum (now the Lincoln Regional Center), state government provided an economic basis for the growth of the new capital city.

Most of Lincoln’s streets were assigned a generous right-of-way 100 feet wide, more than ample in horse and buggy days. But certain streets including 3rd, 7th, 9th, 11th, and 15th, and D, J, O, and S, were laid out on 120 feet of right-of-way. O and 9th Streets were envisioned as commercial corridors, as indicated by the platting of narrow, 25-foot wide lots along them, intended for commercial buildings built lot-line-to-lot-line and sharing party walls. The other extra-wide right-of-ways align with the park, the campus, and the Capitol grounds, providing vistas through the city to the center of these key sites. Today Centennial Mall north of the Capitol, Lincoln Mall to the west, and Goodhue Boulevard to the south make good use of these city-shaping vistas, highlighting the glorious 400-foot Capitol tower.

Where these broad avenues intersected, such as 11th and J (Lincoln Mall) and 11th and D Streets, the wide intersections provide special opportunities. In the early 20th century a 40-foot diameter foundation graced the center of the 11th and J intersection, until newly introduced automobiles (and their newly minted drivers) were less successful in navigating the intersection than horse-drawn vehicles had been. The intersection is still celebrated with circular planters on its four corners. The southwest one displays an enlarged reproduction of the fountain, which was removed to a park in the 1910s. At 11th and D Streets to the south, a mini-roundabout was recently installed to help guide drivers through that extra-wide intersection.

The Original Plat also included a block for a county courthouse west of the Capitol, which remains the location of the County/City Building at 10th and K Streets. At 10th and O Streets, a “Market Square” was provided, but soon was deeded to the federal government as a site for a U. S. Courthouse and Post Office. The City regained the original Post Office at 920 O Street in 1905, after a new federal building was begun on the northeast part of the governmental block. The “new” post office (long known as known as “Old Fed”) eventually filled the north half of that block and continues today as Grand Manse, converted to apartments, a restaurant, and other commercial facilities. The Market Square function was relocated two blocks north to another block dedicated for public uses, now Lincoln Journal Star’s printing and distribution facility.

The Original Plat also provided six blocks for public schools — a high school and five “common” (elementary) schools. The original Lincoln High School operated on the block bounded by M, N, 15th (Centennial Mall) and 16th Streets from 1871 to 1915, when the “new” Lincoln High opened at 21st and J Streets. That handsome Neoclassical Revival style building began its 100th school year in August 2014. Three of the six school sites of the Original Plat still accommodate facilities of Lincoln Public Schools — McPhee Elementary at G Street and Goodhue Boulevard, Everett Elementary at 11th and C Streets, and Park Middle School at 8th and F Street.

Finally, the Original Plat contained notes inviting churches to build in the new capital, on prime corner sites provided free by the State. Ten churches soon sprang up on those downtown sites, and the legislature assisted others on nearby parcels in Lincoln’s early decades, including a Jewish synagogue and two African-American congregations. These churches contributed to the new city’s settlement and growth, and several churches still minister to citywide congregations from downtown locations.

From Lancaster’s population of 30 to Lincoln and Lancaster County’s estimated 300,000 residents of 2015, the city has grown far beyond the Original Plat, but its grid, the University, and the landmark Capitol still unify a lovely city in the prairie.

Recent Comments