Lux Center for the Arts

by Julie Nichols

Last September, eight street artists cast visions on the walls of the University Place neighborhood—swiftly outlining by night then working all day in blistering Nebraska sun. Spent cans of spray paint lay scattered below ladders as artists worked against time. Color bloomed suddenly along North 48th Street in the University Place neighborhood, as if revealing something that belonged there all along.

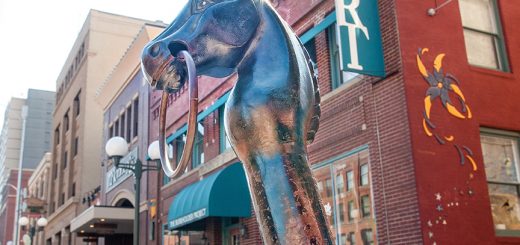

Meet EmergeLNK, a transformative public art project and festival, via LUX Center for the Arts, whose long-time mission of community access and outreach has reached new levels of daring. Street art by definition transgresses public space, pushes boundaries in setting and purpose, and often arises from silenced, misperceived voices. EmergeLNK’s muralists come from varying backgrounds, experience, and training—but they all know the power of the street.

The “placemaking” model adopted for Emerge LNK concentrates art in neighborhoods, engaging inhabitants to center neighborhood identity with art as the backdrop of daily life. Muralist Shawn Dunwoody calls it “Place ACTIVATION”. Dunwoody lived the urban disconnect of poverty and its excess of anxiety. Community collaboration, he believes, is where the art happens, and in this convergence, public art serves as both urban intervention and crucial community development. The richest resource? “The people,” Dunwoody says. “You can list many resources you think would be valuable. But if there’s no connection to and among the artists in a community, it won’t pan out.”

The works are as divergent as their makers are diverse. Self-taught Brazilian artist Eder Muniz (“Street Lizard”) enlivens “non-places” with mashups of humanized animals and fantastical plants in exotic shifts of scale and color, a dialogue between urban and natural environs. Ana Marietta, from Barranquitas, Puerto Rico whose meticulously rendered birds and fish gaze with human intensity. Ana holds a degree in animal science, but her impulse to paint began in her father’s carpentry shop with wood scraps and tempera.

Lakota artist Focus Smith’s work revives connections to ceremony, using Lakota symbols and images relatable to indigenous youth seeking links to tradition. Focus began as a street-tagger and sees graffiti culture as legitimate expression. Omaha-based Watie White, an established printmaker whose works appear in museums and private collections, uplifts community figures with large-scale woodcut portraits. Lincoln multi-media artist Nolan Tredway surprises viewers with playful alien shapes on ivy-framed panels. Yarn-bomber Ishknits wraps trees and building columns, asserting a typically feminine medium into the street art realm.

A self-described ‘art-ivist’ from Rochester, New York, Shawn Dunwoody’s work appears across from bus stops, on buildings and street surfaces in many American cities. Shawn draws inspiration from talking with neighborhood folks, underscoring the collaborative nature of public art. On the back of the LUX main building, Oria Simonini’s first mural, a monumental portrait of a young girl honors the immigrant experience. Simonini is a BFA graduate of UNL, and prefers her immigrant identity to any national origin.

As the pandemic thrust the world into uncertainty in 2020, the LUX adapted. Reluctantly cancelling classes, staff pivoted to on-line instruction, video tutorials and livestreamed artist talks, returning to the classroom only through private lessons with safety protocols. This quick response secured paychecks for artists and staff and reconnected students. During lockdown, public school teachers, paraeducators and LUX staff hand-distributed over 400 free art supply kits and books to children throughout Lancaster County, including the People’s City Mission.

As art moved outdoors, the pandemic ignited serendipitous projects. The LUX opened the Community Art Alley, where anyone can paint on walls between LUX buildings. Nine Nebraska Artists followed, with 9-panel composite woodcut murals wheatpasted on buildings throughout Lincoln. With camps suspended, LUX leaders concocted a kid-friendly drive-through installation. Twenty artists created Underwater, Cave and Forest habitats with kinetic sculptures and fanciful wildlife. Over its two weeks on display, nearly 1,500 visitors walked or drove through Art Safari. Shortly after, the EmergeLNK mural and Street Art Festival took shape.

Ten months later, it materialized. As the pandemic slowed, everyone itched for a resurrection, and EmergeLNK meant to celebrate arising after a dark year. The pandemic raged on. The murals went up anyway, as if to say ‘we are still here’.

The LUX Center for the Arts began in 1977 as University Place Art Center, a modest cultural focal point for the neighborhood. In 1987, artist-educator Gladys Lux donated the old University Place City Hall specifically to provide space for art to grow. In 2000, the center changed its name to honor Gladys Lux’s passion and generosity.

Gladys Lux’s desire to make art universally available remains core to the LUX mission and has grown from that root. The LUX reaches more students than any arts organization in Nebraska—through studio classes for all ages, after school programs, mobile outreach programs, artists’ residencies and scholarships. This palette of community interface includes after-school programs, artmaking for cancer survivors and incarcerated youth, and low-income children through robust support of Title 1 Schools.

Offering year-round classes in ceramics, painting, drawing, mixed media, glass and metalworking, high-quality instruction distinguishes the LUX. Artists-in-residence serve as instructors, also receiving studio space, materials and solo exhibitions. LUX reaches over 2,000 students annually, and awards over 50 youth scholarships each year. In 2020, LUX paid nearly $100,000 directly to working artists.

With nearly 40 exhibitions annually, including quarterly shows of Gladys Lux’s stunning print collection, the LUX draws at least 8,000 visitors per year. The LUX has built momentum over the last two decades, expanding facilities and classes. In 2000, an adjacent building was purchased for a ceramics center, adding two classrooms, four studios and doubling capacity for artists’ residencies. The center houses a student gallery, ceramics classrooms for throwing and handbuilding; kiln, glazing and mixing rooms and an outdoor gas kiln. Renovation of the 103-year-old main building added more classrooms, updated utilities, and built a dedicated Community Gallery for LUX students, local guilds, and college-level artists from nearby Nebraska Wesleyan and UNL.

When George Floyd’s death unveiled the anguish felt by communities of color caught in systems that feed inequity, the LUX further galvanized its mission to provide healing and economic opportunity to communities damaged by generational poverty, cultural traumas, and embedded social barriers. With established outreach, the LUX continues to actively promote, inspire, and lead efforts to make lasting change through art.

With EmergeLNK’s success, the LUX’s crusade to fill Northeast Lincoln with as many as 30 murals over the next six years represents its most ambitious public work to date. LUX plans installation of two or more each year, providing a vibrant, walkable destination for visitors and neighborhood residents.

At the EmergeLNK Street Art Festival, Executive Director Joe Shaw marveled at what he considers vital success. Drawn to the color, music, and custom cars, neighbors who had walked past the LUX for years came out. “If I heard ‘I’ve never been here before’ once, I heard it a hundred times. Too many to count,” Shaw said, beaming. “Our neighbors crossed the street for the very first time.”

Showing established artists alongside emerging talent can be a balancing act, but LUX maintains prestige while amplifying alternative voices. “Street art has become increasingly legitimized,” says Shaw, “And its proliferation shows it needs to enter the zone of “lauded” artforms.” If his wish is granted, the density of public art will make Northeast Lincoln the city’s most vibrant art district, and the LUX a lodestone for visitors.

Gladys Lux’s mission to connect all people through art abides. The LUX has evolved into a palpable neighborhood presence—a visible pledge to inclusion. Northeast Lincoln’s murals may be blossoms of quiet but radical change.

“The neighborhood owns it,” says Shaw. “All of us can see it, but the art belongs to the people who live here.” Public art cultivates collective identity. As Angela Davis said, “‘Radical’ simply means ‘grasping things by the root.’” The LUX has a loving and firm grip on Lincoln’s community roots, and the foresight and passion to nourish them.

For information on hours, upcoming shows and mural maps, see LUXcenter.org.

Recent Comments